Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems 2nd Edition by Robert Hocken, Paulo Pereira ISBN 1138076899 978-1138076891

$70.00 Original price was: $70.00.$35.00Current price is: $35.00.

Instant download Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems Second Edition after payment

Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems 2nd Edition by Robert Hocken, Paulo Pereira – Ebook PDF Instant Download/Delivery: 1138076899, 978-1138076891

Full download Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems 2nd edition after payment

Product details:

ISBN 10: 1138076899

ISBN 13: 978-1138076891

Author: Robert Hocken, Paulo Pereira

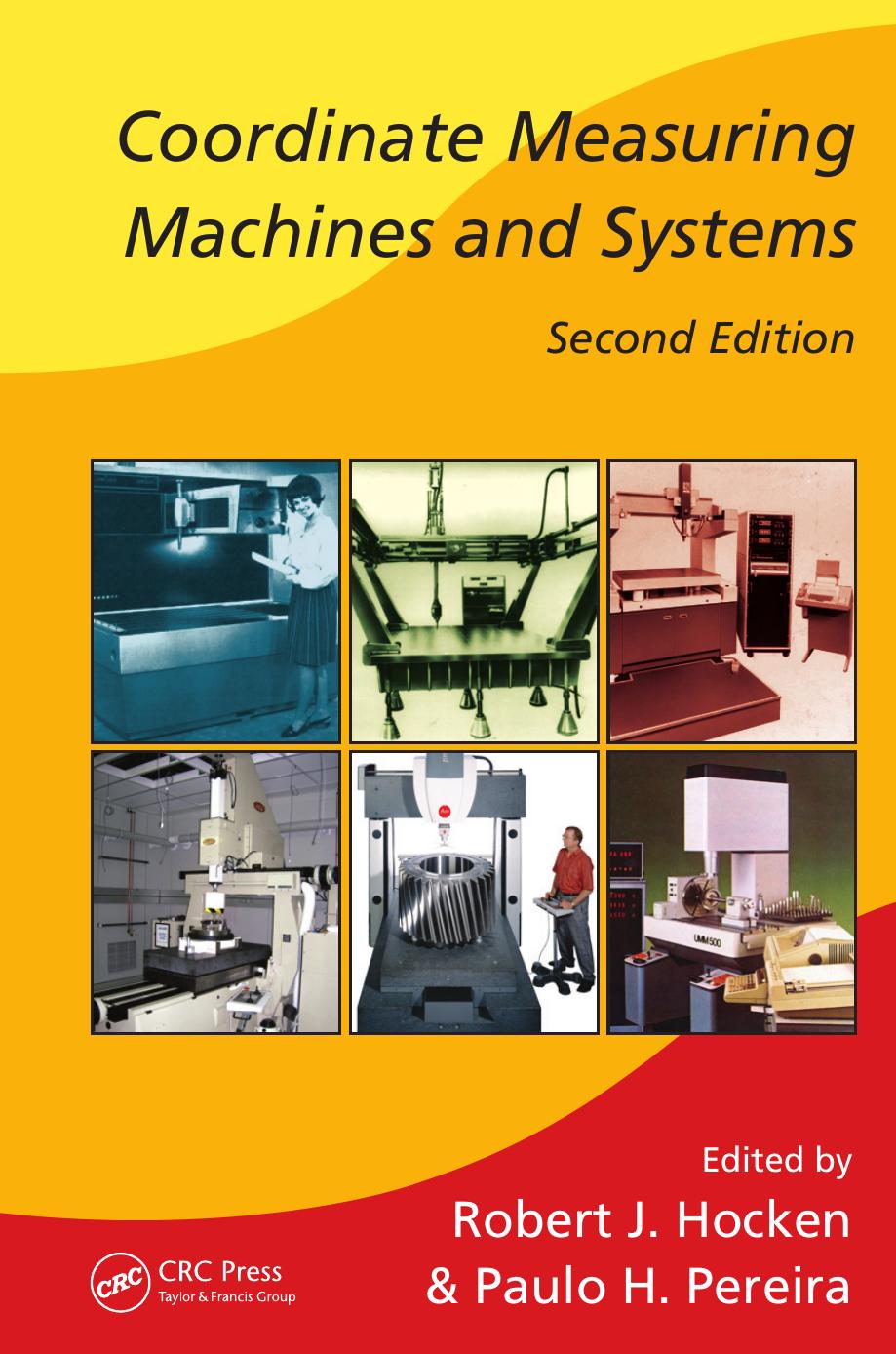

Since John Bosch edited and published the first version of this book in 1995, the world of manufacturing and coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) and coordinate measuring systems (CMSs) has changed considerably. However, the basic physics of the machines has not changed in essence but have become more deeply understood. Completely revised and updated to reflect the change that have taken place in the last sixteen years, Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems, Second Edition covers the evolution of measurements and development of standards, the use of CMMs, probing systems, algorithms and filters, performance and financial evaluations, and accuracy.

See What’s New in the Second Edition:

- Explores the rising expectations of the user for operator interfaces, ease of use, algorithms, speed, communications, and computational capabilities

- Details the expansion of machines such as the non-Cartesian CMM in market share and their increase in accuracy and utility

- Discusses changes in probing systems, and the number of points they can deliver to ever more sophisticated software

- Examines the pressures created by new applications to improve machine performance

The book features two new editors, one from academia and one from a metrology intensive user industry, many new authors, and known experts who have grown with the field since the last version. Furnishing case studies from a wide range of installations, the book details how CMMs can best be applied to gain a competitive advantage in a variety of business settings.

Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems 2nd Table of contents:

Chapter 1 Evolution of Measurement

1.1 Pyramids Provide Evidence of Early Measuring Skills

1.1.1 The Cubit—One of the Earliest Units of Measure

1.2 Accuracy In Navigation Is Basis For The Micrometer

1.2.1 Gage Blocks satisfy Need for Measuring References

1.2.2 Early Comparators Set New Standards for Accuracy

1.3 Interchangeable Parts Gain International Recognition

1.4 Dial Indicator Simplifies Measuring

1.5 Automobile Accelerates Developments In Metrology

1.5.1 Reed Mechanism Provides Greater Shop Floor Precision

1.5.2 Air Gaging Proves Effective for Checking Tight Tolerance Parts

1.5.3 Electronic Gaging Expands Capability for Process Control

1.5.4 Machine Tools Evolve into Early Coordinate Measuring Machines

1.6 First Coordinate Measuring Machine Developed As Aid To Automated Machining

1.6.1 Sheffield Introduces Coordinate Measuring Machines to the North American Market

1.6.2 Digital Electronic Automation Is First Company Formed to Produce Coordinate Measuring Machines

1.6.3 Coordinate Measuring Machine Developments Initiated in Japan by Mitutoyo

1.6.4 Touch-Trigger Probes Expand Versatility of Coordinate Measuring Machines

1.6.5 Software Becomes Essential to Coordinate Metrology

1.6.6 Carl Zeiss Contributions to Coordinate Metroeogy

1.6.7 Coordinate Measuring Machine Industry Follows Traditional Business Patterns

1.7 Summary

Acknowledgments

Chapter 2 The International Standard of Length

2.1 Definition of The Meter

2.1.1 Realization of the International System of Units: Unit of Length

2.1.2 Laser Displacement Interferometry

2.1.3 International Comparison of Artifacts

2.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Measurement Traceability

2.2.1 The Physical Chain of Traceability

2.2.2 Documentary Standards Defining Traceability

2.2.3 The Old and the New Traceabiuty

2.2.4 Traceability in Coordinate Measuring Machines— Task-Specific Measurement Uncertainty

2.3 A Note On Customary Units of Length In The United States

2.4 Summary

Chapter 3 Specification of Design Intent Introduction to Dimensioning and Tolerancing

3.1 Geometric Tolerancing

3.1.1 Principle Elements of Geometric Tolerancing

3.1.1.1 Zones

3.1.1.2 Datums

3.1.1.3 Basic Dimensions

3.1.2 Types of Tolerances

3.1.2.1 Form

3.1.2.2 Orientation

3.1.2.3 Profile

3.1.2.4 Runout

3.1.2.5 Size

3.1.2.6 Location

3.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Inspection of Geometric Tolerances

3.2.1 Physical Interpretation

3.2.2 Algorithms for Point Data

3.3 Y14.5-2009

Chapter 4 Cartesian Coordinate Measuring Machines

4.1 Coordinate Metrology

4.2 Basic Coordinate Measuring Machine Configurations

4.2.1 Moving Bridge

4.2.2 Fixed Bridge

4.2.3 Cantilever

4.2.4 Horizontal Arm

4.2.5 Gantry

4.2.6 Other Configurations

4.3 Hardware Components

4.3.1 Structural Elements

4.3.2 Bearing Systems

4.3.3 Drive Systems

4.3.3.1 Rack-and-Pinion Drive

4.3.3.2 Belt Drive

4.3.3.3 Friction Drive

4.3.3.4 Leadscrew Drive

4.3.3.5 Linear Motor Drive

4.3.4 Displacement Transducers

4.3.4.1 Transmission Scale

4.3.4.2 Reflection Scale

4.3.4.3 Interferential Scale

4.3.4.4 Laser Interferometer Scale

4.4 Control system for coordinate measuring machines

4.5 Summary

Acknowledgments

Chapter 5 Operating a Coordinate Measuring Machine

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Before Starting

5.2.1 Safety

5.2.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Start-Up

5.2.3 Reviewing the Drawing

5.2.4 Choosing Probes

5.2.5 Fixturing

5.2.6 Record Keeping

5.3 Developing The Measurement Program

5.3.1 Qualification

5.3.2 Alignment

5.3.3 Inspection

5.3.4 Analysis

5.3.5 Reporting

5.3.6 Test Run

5.3.7 Enhancing the Program

5.4 Other Resources

5.5 Conclusion

Chapter 6 Probing Systems for Coordinate Measuring Machines

6.1 Purposes and basics of probing

6.1.1 Probing Process

6.1.1.1 The Positioning Step

6.1.1.2 The Probing Step

6.1.1.3 The Measuring Step

6.1.1.4 The Evaluating Step

6.1.2 History of Probing Systems

6.1.3 Basic Configuration of a Tactile Probing System

6.1.4 Classification of Probing Systems for Coordinate Measuring Machines

6.1.4.1 Contact Detection

6.1.4.2 Operational Principle

6.1.4.3 Mode of Operation

6.1.4.4 Probing Force Generation

6.1.4.5 Kinematics

6.1.4.6 Size of Probing Element and Feature to Be Measured

6.2 Practical aspects

6.2.1 Principles of Displacement Measurement

6.2.1.1 Inductive Systems

6.2.1.2 Capacitive Systems

6.2.1.3 Resistive Systems

6.2.1.4 Optical Systems

6.2.1.5 Scale-Based Systems

6.2.2 Probing Element

6.2.3 Influences on Probing Performance

6.2.3.1 Probing System Qualification

6.2.3.2 Environmental Influences

6.2.3.3 Wear and Deformation

6.2.3.4 Pretravel and Overtravel

6.2.4 Probing Error

6.2.5 Multisensor Coordinate Measuring Machines

6.2.6 Probing Systems for Coordinate Measuring Machines

6.2.6.1 The Renishaw Revo Five-Axis Measuring Head

6.2.6.2 Zeiss VAST Navigator

6.2.7 Probing Systems for Measuring Microparts

6.2.7.1 Scanning Probe Microscope-Based Microprobing Systems

6.2.7.2 Tactile Microprobing Systems

6.3 Probing System Accessories

6.3.1 Accessory Elements for Improving Accessibility

6.3.2 Accessory Elements for Improving Navigation

6.3.3 Accessory Elements for Automation

6.4 Summary

Chapter 7 Multisensor Coordinate Metrology

7.1 From Profile Projector To Optical-Tactile Metrology

7.2 Visual Sensors For Coordinate Measuring Machines

7.2.1 Optical Edge Sensor

7.2.2 Image Processing Sensor

7.2.3 Illumination for Visual Sensors

7.2.4 Distance Sensors

7.2.5 Autofocus

7.2.6 Laser Point Sensors

7.2.7 Multidimensional Distance Sensors

7.2.8 Multisensor Technology

7.3 Computer Tomography

7.3.1 Principle of X-Ray Tomography

7.3.2 Multisensor Coordinate Measuring Machines with X-Ray Tomography

7.3.3 Accurate Measurements with Computer Tomography

7.3.4 Measuring a Plastic Part

7.4 Measuring Accuracy

7.4.1 Specification and Acceptance Testing

7.4.2 Measurement Uncertainty

7.4.3 Correlation among Sensors

7.5 Outlook

Chapter 8 Coordinate Measuring System Algorithms and Filters

8.1 Curve And Surface Fitting

8.1.1 Least Squares Fits

8.1.2 Minimum-Zone Fits

8.1.3 Minimum Total Distance (L1) Fits

8.1.4 Minimum-Circumscribed Fits

8.1.5 Maximum-Inscribed Fits

8.1.6 Other Fit Objectives

8.1.7 General Shapes

8.1.8 Weighted Fitting

8.1.9 Constrained Fitting

8.1.10 Fit Objective Choices

8.2 Stylus Tip Compensation

8.3 Data Filtering

8.3.1 Convolution Filters

8.3.2 Morphological Filters

8.4 GD&T, Datums, and Local Coordinate Systems

8.4.1 Flatness Example

8.4.2 Datum Reference Frames

8.4.3 More Complex Datum Reference Frames

8.5 Data Reduction

8.6 Software Testing

8.7 Conclusion

8.8 Annex—Residual Functions For Basic Geometric Shapes

Chapter 9 Performance Evaluation

9.1 Measurement Error And Uncertainty

9.1.1 Combined Standard Uncertainty

9.1.2 Expanded Uncertainty and Level of Confidence

9.1.3 Impact of Measurement Uncertainty

9.2 Overview of The Coordinate Measuring Machine Measurement Process

9.2.1 Software Performance (Algorithm Implementation)

9.2.2 Fitting Criteria (Algorithm Selection)

9.2.3 Sampling Strategy

9.2.3.1 Workpiece Geometry

9.2.3.2 Sensitivity to Measurement and Workpiece Errors

9.2.4 Coordinate Measuring Machine Hardware Performance

9.2.4.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Geometry

9.2.4.1.1 Rigid-Body Errors

9.2.4.1.2 Uncertainty in Rigid-Body Errors

9.2.4.1.3 Structural Distortions

9.2.4.1.4 CMM Dynamic Errors

9.2.4.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Probing System

9.2.4.2.1 Stylus Ball Size

9.2.4.2.2 Probe Lobing

9.2.4.2.3 Multiple Styli

9.2.4.2.4 Probe/Stylus Changing

9.3 Quantifying Coordinate Measuring Machine Performance

9.3.1 Artifacts and Their Mounting

9.3.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Standards

9.3.2.1 Interpreting Standardized Specifications

9.3.2.2 Recent Trends in Coordinate Measuring Machine Standards

9.3.2.3 Decision Rules Used in Coordinate Measuring Machine Standards

9.3.2.4 International Standard ISO 10360 and ASME B89.4.10360 (2008)

9.3.2.5 ASME B89.4.1M (1997 with 2001 Supplements)

9.3.2.5.1 Repeatability

9.3.2.5.2 Linear Displacement Accuracy

9.3.2.5.3 Volumetric Performance (General)

9.3.2.5.4 Volumetric Performance Test

9.3.2.5.5 Volumetric Performance Using Offset Probes

9.3.2.5.6 Volumetric Performance for Rotary Table Coordinate Measuring Machines

9.3.2.5.7 Bidirectional Length Test

9.3.2.5.8 Probing Performance

9.3.2.6 VDI/VDE 2617 Standard

9.3.2.6.1 One-Dimensional Length Measuring Uncertainty (uv)

9.3.2.6.2 Two-Dimensional Length Measuring Uncertainty (u2)

9.3.2.6.3 Three-Dimensional Length Measuring Uncertainty (u3)

9.3.2.6.4 Probe Performance

9.3.2.6.5 Rotary Table Tests

9.3.2.7 CMMA Standard

9.3.3 Machine Tools Used as Coordinate Measuring Machines

9.3.4 Methods for the Estimation of Measurement Uncertainty

9.3.4.1 Measurement Uncertainty Using CMM Standards

9.3.4.2 Measurement Uncertainty Using Comparison Methods

9.3.4.2.7 Cage Repeatability and Reproducibility Issues

9.3.4.3 Measurement Uncertainty Using Monte Carlo Software

9.3.5 Interim Testing

9.4 Summary

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

Chapter 10 Temperature Fundamentals

10.1 Thermal Effects Diagram

10.2 The 20°C Reference Temperature

10.3 Average Temperatures Other Than 20°C

10.3.1 Uncertainties of Coefficients of Thermal Expansion

10.4 Nonuniform Temperature

10.4.1 Gradients—Thermal Variations in Space

10.4.2 Temperature Variation—Thermal Variations in Time

10.4.3 Dynamic Effects of Thermal Variations

10.4.4 Thermal Memory from a Previous Environment

10.4.4.1 Soak Out Experiments

10.5 Drift Test

10.5.1 Drift of Coordinate Measuring Machines

10.5.2 Transducer Drift Check

10.5.3 Thermal Drift of Laser Interferometers

10.6 Thermal Error Index

10.6.1 Example of the Thermal Error Index

10.6.2 Features of Thermal Error Index

10.6.3 International Organization for Standardization Use of Thermal Error Index

10.7 Reducing The Thermal Error Index

10.7.1 Compensation of the Machine

10.7.1.1 Limitations of Finite Element Analysis

10.7.2 Part Compensation versus Temperature Control

10.7.3 Direct Temperature Control

10.7.3.1 Modern Machine Tools Boxes

10.7.3.2 Thermally Optimized Factory

10.7.3.3 Coordinate Measuring Machine Boxes

10.7.3.4 Coordinate Measuring Machine Manufacturers Boxes

10.7.3.5 Coordinate Measuring Machines and the Lead of Machine Tools

10.8 Design of Temperature-Controlled Rooms

10.9 Relationship Between Reference And Workpiece Temperatures

10.10 Summary

10.10.1 Near-Term Actions to Reduce Thermal Error Index

10.10.2 Long-Term Actions to Reduce the Thermal Error Index

Appendix: How Measurement of Temperature Affects The Measurement of Length

Chapter 11 Environmental Control

11.1 Importance of Temperature Control

11.1.1 Temperature Control

11.1.1.1 Direction of Airflow

11.1.1.2 Entrance and Egress of Airflow

11.1.1.3 Velocity and Volume of Airflow

11.1.1.4 Mode of Temperature Regulation

11.1.1.5 Location of Temperature Sensors

11.1.1.6 Air Lock or Soak Out Room

11.1.2 Common Practices to Reduce Thermal Influences

11.1.2.1 Reducing Radiation Effects

11.1.2.2 Reducing Convection Effects

11.1.2.3 Reducing Conduction Effects

11.1.2.4 General Methods

11.1.3 Temperature Recording

11.2 Humidity Control

11.3 Dust Control

11.4 Vibration Isolation Treatments

11.4.1 The Need for Vibration Isolation

11.4.2 Sources of External Disturbing Vibrations

11.4.2.1 Source

11.4.2.2 Path

11.4.2.3 Receiver

11.4.3 Vibration Isolation System Types and Characteristics

11.4.3.1 Passive Isolators: Pads

11.4.3.2 Passive Isolators: Springs

11.4.3.3 Passive Isolators: Air Springs

11.4.4 Inertia Bases

11.4.5 Vibration Specifications

11.5 Sound Level Control

11.6 Other Considerations

11.7 Summary

Chapter 12 Error Compensation of Coordinate Measuring Machines

12.1 Classifications of Error Compensation Techniques

12.1.1 Real-Time and Non-Real-Time Error Compensations

12.1.2 Software and Hardware Error Compensations

12.1.3 Error Compensation, Error Correction, and Error Separation

12.2 Key Techniques of Coordinate Measuring Machine Error Compensation

12.2.1 Establishment of Mathematical Model

12.2.2 Machine Calibration

12.2.3 Compensation Software and Device

12.3 Mathematical Model of Machine Errors

12.3.1 Quasi-Rigid Body Model of FXYZ Type Machine

12.3.2 Geometric Models for Other Types of Machines

12.3.3 Verification for Quasi-Rigid Body Assumption Model

12.3.4 Geometric Model of a Machine That Does Not Obey the Axis Independence Assumption

12.3.5 Geometric Model of Coordinate Measuring Machines with a Rotary Table

12.3.6 Thermal Model of the Coordinate Measuring Machine

12.4 Application Problems of Error Compensation Techniques In Coordinate Measuring Machines

12.4.1 Prerequirements

12.4.2 Verification and Troubleshooting

12.4.3 Limitations

12.5 Trends In Error Compensation Development

Chapter 13 “Reversal” Techniques for Coordinate Measuring Machine Calibration

13.1 Classic Reversals

13.2 Self-Calibration On Coordinate Measuring Machines

13.3 Summary

Chapter 14 Measurement Uncertainty for Coordinate Measuring Systems

14.1 Background

14.2 Examples

14.2.1 Metrology Planning for a New Manufacturing Cell

14.2.1.1 Machine Uncertainty

14.2.1.2 Sampling Uncertainty

14.2.1.3 Uncertainty Due to Temperature

14.2.1.4 Datum Uncertainty

14.2.2 Other Exampees

14.3 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Chapter 15 Application Considerations

15.1 Hardware Capability

15.1.1 Measuring Volume, Machine Configuration, and Part Weight

15.1.1.1 Sizing Recommendations

15.1.1.2 Machine Configuration

15.1.1.3 Part Weight

15.1.2 Measuring Accuracy

15.1.2.1 Accuracy and Repeatability

15.1.2.2 Uncertainty Budget

15.1.3 Traceability and Uncertainty for Part Measurements

15.1.4 Speed or Throughput

15.1.5 Probe Types

15.1.5.1 Contact Probes

15.1.5.2 Non-Contact Sensors

15.2 Software Capability

15.2.1 Programming Routines

15.2.1.1 Advantages of Programmable CMMs

15.2.1.2 Teach Programming

15.2.1.3 Parametric Programming

15.2.1.4 Off-Line Programming

15.2.2 Operator Interfaces

15.2.3 Data Evaluation Systems

15.2.4 Data Output Formats

15.2.5 Data Interfaces

15.3 Other Considerations

15.3.1 People or Training Requirements

15.3.2 Part Handling, Probing, and Fixturing

15.3.3 Environmental Conditions

15.3.3.1 Part Cleaning

15.3.3.2 Temperature

15.3.3.3 Vibration

15.3.3.4 Humidity

15.3.3.5 Electrical Power

15.3.3.6 Compressed Air

15.3.4 Sampling Strategy

15.3.4.1 Part Sampling (Inspection Frequency)

15.3.4.2 Point Sampling

15.3.5 Layout or Workflow

15.3.6 Warranty and Maintenance

15.3.7 Information Sources

15.3.8 Metrology Services Outsourcing

15.4 System Cost

15.5 Summary

Acknowledgments

Chapter 16 Typical Applications

16.1 Case Study 1: Location of Cooling Holes In Hollow, Cast, And Turbine Airfoils

16.1.1 Airfoil Inspection Equipment

16.1.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.1.3 Quality Assurance

16.1.4 Data Handling

16.1.5 Calibration and Reverification

16.1.6 Measurement Uncertainty

16.1.7 Summary

16.2 Case Study 2: Gear Measurement With Coordinate Measuring Machines On The Shop Floor

16.2.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.2.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.2.3 Organization

16.2.4 Data Handling

16.2.5 Periodic Inspection of Coordinate Measuring Machines

16.2.6 Measurement Uncertainty†

16.2.7 Summary

16.3 Case Study 3: Applications of Large Coordinate Measuring Machines In Industries

16.3.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.3.2 Workpieces and Their Handling

16.3.3 Data Handling

16.3.4 Periodic Inspection of Measuring Machine Capability

16.3.5 Organization

16.3.6 Summary

16.4 Case Study 4: Leitz Pmm-F Inspects Wind Energy Plant Components

16.4.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.4.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.4.3 Organization

16.4.4 Data Handling

16.4.5 Periodic Inspection of Coordinate Measuring Machines

16.4.6 Measurement Uncertainty

16.4.7 Summary

16.5 Case Study 5: Untended Automation Cells

16.5.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.5.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.5.3 Organization

16.5.4 Data Handling

16.5.5 Periodic Inspection of Coordinate Measuring Machines

16.5.6 Measurement Uncertainty

16.5.7 Summary

16.6 Case Study 6: Geometry Measurement of Cast Aluminum Cylinder Heads Using Industrial Computed Tomography

16.6.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.6.2 Workpiece and Measuring Task

16.6.3 Data Handling

16.6.4 Accuracy Enhancements

16.6.5 Periodic Inspection of Measuring Machine Capability

16.6.6 Measurement Uncertainty Study

16.6.7 Summary

16.7 Case Study 7: Noncontact Measurement of Sculptured Surface of Rotation

16.7.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.7.2 Workpieces and Their Handung

16.7.3 Data Handung

16.7.4 Periodic Inspection of Measuring Machine Capability

16.7.5 Organization

16.7.6 Summary

16.8 Case Study 8: Measuring Precision Medical Prostheses

16.8.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.8.2 Workpieces and fixtures

16.8.3 Organization

16.8.4 Data Handung

16.8.5 Periodic Inspection of Coordinate Measuring Machines

16.8.6 Measurement Uncertainty

16.8.7 Summary

16.9 Case Study 9: Precision Coordinate Measuring Machine For Calibration of Length Standards And Master Gages

16.9.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.9.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.9.3 Organization

16.9.4 Data Handling

16.9.5 Periodic Inspection of Coordinate Measuring Machines

16.9.6 Measurement Uncertainty

16.9.7 Summary

16.10 Case Study 10: Measurement of an Image Slicer Mirror Array, Using The Isara Ultraprecision Coordinate Measuring Machine

16.10.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.10.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.10.3 Data Handling

16.10.4 Measurement Uncertainty

16.10.5 Summary

16.11 Case Study 11: Ultraprecision Micro-Coordinate Measuring Machine For Small Workpieces

16.11.1 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.11.2 Workpieces and Fixtures

16.11.3 Organization

16.11.4 Data Handling

16.11.5 Calibration and Correction of the Micro-Coordinate Measuring Machine

16.11.6 Performance Verification

16.11.7 Measurement Uncertainty

16.11.8 Summary

16.12 Case Study 12: Measurements of Large Silicon Spheres Using A Coordinate Measuring Machine

16.12.1 Introduction

16.12.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Equipment

16.12.3 Measurement Achievement

16.12.4 Measurement Method

16.12.5 Measurement Procedure

16.12.6 Summary

Acknowledgments

Chapter 17 Non-Cartesian Coordinate Measuring Systems

17.1 Introduction

17.2 Articulated Arm Coordinate Measuring Machines

17.2.1 Working Principle

17.2.2 Construction Realization

17.2.3 Accuracy Analysis

17.2.3.1 Errors of the Angular Encoders

17.2.3.2 Squareness Errors

17.2.3.3 Error Motions of the Articulated Arm

17.2.3.4 Thermal Errors

17.2.3.5 Elastic Deformations of Rods

17.2.3.6 Probing Error

17.2.3.7 Calibration Errors

17.2.4 Performance Evaluation of Articulated Arm Coordinate Measuring Machines

17.2.4.1 Effective Diameter Performance Test (B89.4.22, Section 5.2)

17.2.4.2 Single-Point Articulation Performance Test (B89.4.22, Section 5.3)

17.2.4.3 Volumetric Performance Test (B89.4.22, Section 5.4)

17.3 Triangulation Systems

17.3.1 Theodolite Systems

17.3.1.1 Working Principle

17.3.1.2 Accuracy Analysis

17.3.2 Photogrammetry

17.3.2.1 Working Principle

17.3.2.2 Camera Calibration

17.3.2.3 Image Matching

17.3.2.4 Accuracy Analysis

17.3.3 Light Pen Coordinate Measuring Machine

17.3.3.1 Working Principle

17.3.3.2 Accuracy Analysis

17.4 Spherical Coordinate Measuring Systems

17.4.1 Laser Tracker

17.4.1.1 Working Principle

17.4.1.2 Target Component

17.4.1.3 Tracking System

17.4.1.4 System Calibration

17.4.1.5 Accuracy Analysis

17.4.2 Systems Based on Absolute Distance Measurement

17.4.2.1 Time-of-Flight Measuring Systems

17.4.2.2 Phase Difference Measuring System

17.4.3 Performance Evaluation of Laser-Based Spherical Coordinate Measurement Systems

17.5 Multilateration Systems

17.5.1 Working Principle

17.6 Summary

Chapter 18 Measurement Integration

18.1 Selection Factors

18.2 Coordinate Measuring Machine Measurements In The Manufacturing Process

18.2.1 Preprocess Measurement and Analysis

18.2.2 In-Process Measurements

18.2.3 Process-Intermittent Measurements

18.2.4 Postprocess Measurements

18.3 Summary

Acknowledgments

Chapter 19 Financial Evaluations

19.1 Strategic Implications Pertaining To Measurement

19.1.1 Measurement Serves Different Objectives in Industry

19.1.2 Coordinate Measuring Machines for Process Control

19.1.2.1 Uncertainty Reduction with Standard Computerized Equipment for Statistical Process Control

19.1.2.2 Optimum Measurement Plan Using Coordinate Measuring Machines

19.1.3 Standard Coordinate Measuring Machines for Process Control

19.1.4 Alternate Measurement Approaches for Process Control

19.1.4.1 On-Machine Probing

19.1.4.2 Dedicated Gaging

19.1.5 Flexible Inspection Systems

19.1.6 Acceptance of Coordinate Measuring Machines for Process Control in Industry

19.2 Technical Requirements Are Critical

19.2.1 Functional Tolerances Required for Zero-Defect Manufacturing

19.2.1.1 Analytical Measurements with Coordinate Measuring Machines to Establish Functional Tolerances

19.2.2 Process Control Uncertainty Contribution to Overall Process Uncertainty

19.3 Financial Analysis Involves Many Factors

19.3.1 Comparison of Measurement Costs Per Workpiece

19.3.1.1 Fixed Costs

19.3.1.2 Variable Costs

19.3.2 Determining Return on Investment for Direct Computer-Controlled Coordinate Measuring Machines

19.3.2.1 Scrap and Rework Reduction

19.3.3 A Sample Process Control Cost Comparison

19.3.4 Sample Gage and Fixture Calibration Cost Comparison

19.3.5 Net Present Value Calculations

19.4 Summary

Acknowledgments

References

Bibliography

Index

People also search for Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems 2nd :

coordinate measuring machines and systems second edition

coordinate measuring machines and systems second edition pdf

what is coordinate measuring machine

what is a coordinate measuring machine used for

coordinate measuring machine definition

Tags: Robert Hocken, Paulo Pereira, Coordinate Measuring